Joan of ArcJehanne D'Arc

Lest we forget

Her dreams to give her heart away like an orphan on a wave,

She cared so much she offered up her body to the grave.O.M.D.

In a two year military campaign inspired by her faith and driven by love of her country, a seventeen year old maiden from an obscure town in the east of France determined the future not only of France but also Europe and beyond. France, divided, assailed by English and Burgundian forces, saw Charles, the last of the Valois monarchs, desperate enough to grant a seventeen year old maiden a position of leadership in the wars waged for his kingdom. Faith and Courage earned this maiden the trust and devotion of an army. Born on January 6th, 1412 to Jacques and Isabelle d'Arc in the village of Domremy, now Domremy-la-Pucelle, on France's eastern border, Joan grew up well aware of events in France and these events would set the stage for Joan's brief life and death that would lead to martyrdom. It was around 1424, at age twelve, that she began to experience visions of Saints and Angels which she could touch and who communicated verbally to her. These visions Joan identified as St. Catherine of Alexandria, St. Margaret of Antioch, the Archangel Michael, the messenger Gabriel and sometimes groups of Angels. Although at the time of her birth a truce was still in effect between France and England, an internal war had erupted between two factions of the French Royal family and this destabilising conflict made it easier for the English to invade once more. One side, called the "Orleanist" or "Armagnac" faction, was led by Count Bernard VII of Armagnac and Duke Charles of Orleans, whom Joan would later say was greatly beloved by God. Their rivals, known as the "Burgundians", were led by Duke John-the-Fearless of Burgundy. The forces of his son, Philip III, would later capture Joan and hand her over to the English. One of his supporters, a pro-Burgundian clergyman and English advisor named Pierre Cauchon, would later arrange her conviction on their behalf. While the French remained divided into warring factions, diplomats failed to extend the truce with England. King Henry V, citing his family's old claim to the French throne, promptly invaded France in August of 1415 and defeated an Armagnac-dominated French army at the battle of Agincourt on October 25th. The English returned in 1417, gradually conquering much of northern France and gaining the support in 1420 of the new Burgundian Duke, Philip III, who agreed to recognize Henry V as the legal heir to the French throne while rejecting the rival claim of the man whom Joan would consider the rightful successor, Charles of Ponthieu (later known as Charles VII), the last heir of the Valois dynasty which had ruled France since 1328. Charles gradually lost the allegiance of all the towns north of the Loire River except for Tournai in Flanders and Vaucouleurs, near Domremy. Since Paris had been controlled by the opposite faction since 1418, his court was now located in the city of Bourges in central France, hemmed in by hostile forces on nearly every side: pro-English Brittany to the northwest,English-occupied Normandy to the north, the Burgundian hereditary domains of Flanders, Artois, Burgundy, Franche-Comte and Charolais to the northeast and east and the English hereditary domain of Aquitaine to the southwest. In 1428 the situation became critical as the English gathered troops for a campaign into the Loire River Valley northern perimeter of Charles' dwindling territory. The city of Orleans on the Loire now became the primary focus. It was at this moment that an unexpected turn of events began to unfold. Joan said that for some time prior to 1428 the saints in her visions had been urging her to "go to France" (in its original  feudal sense - the direct Royal domain) and drive out the English and Burgundians, explaining that God supported Charles' claim to the throne, supported Orleans' captive overlord Duke Charles of Orleans and had taken pity on the French population for the suffering they had endured during the war. She said that during her childhood these visions had merely instructed her to "be or pious, to go to church regularly" but over the next several years they had persistently called for her to go to the local commander at Vaucouleurs to obtain an escort to take her to the Royal Court. feudal sense - the direct Royal domain) and drive out the English and Burgundians, explaining that God supported Charles' claim to the throne, supported Orleans' captive overlord Duke Charles of Orleans and had taken pity on the French population for the suffering they had endured during the war. She said that during her childhood these visions had merely instructed her to "be or pious, to go to church regularly" but over the next several years they had persistently called for her to go to the local commander at Vaucouleurs to obtain an escort to take her to the Royal Court.  She embarked on the latter course in May of 1428, not long before large English reinforcements landed in France for deployment in the Loire Valley. Joan arranged for a family relative, Durand Lassois, to take her to see Lord Robert de Baudricourt, who had remained loyal to the Armagnacs despite his status as a vassal of the pro-Burgundian Duke of Lorraine. Baudricourt refused to listen to her and she returned home. Shortly after her return, in July of 1428 Domremy found itself in the path of a Burgundian army led by Lord Antoine de Vergy, forcing the villagers to take refuge in the nearby city of Neufchateau until the troops had passed. Vergy's army laid siege to Vaucouleurs and induced Baudricourt to pledge neutrality. A few months later on October 12th, Orleans was placed under siege by an English army led by the Earl of Salisbury. The eyewitness accounts and other 15th century sources say that the situation for Charles was rather hopeless by that stage. His treasury at one point was down to less than "four ecus" and his armies were a motley collection of local contingents and foreign mercenaries and he himself, according to the surviving accounts, was torn with doubt over the validity of his cause - since his own mother, cooperating with the English, had allegedly declared him illegitimate in order to deny his claim to the throne. Orleans, the last major city defending the heart of his territory, was in the grip of an English army. Someone out of the ordinary was needed to reverse the fortunes and revive the failing cause of the last Valois and that someone was just setting out on a most improbable journey to take her place in history. She embarked on the latter course in May of 1428, not long before large English reinforcements landed in France for deployment in the Loire Valley. Joan arranged for a family relative, Durand Lassois, to take her to see Lord Robert de Baudricourt, who had remained loyal to the Armagnacs despite his status as a vassal of the pro-Burgundian Duke of Lorraine. Baudricourt refused to listen to her and she returned home. Shortly after her return, in July of 1428 Domremy found itself in the path of a Burgundian army led by Lord Antoine de Vergy, forcing the villagers to take refuge in the nearby city of Neufchateau until the troops had passed. Vergy's army laid siege to Vaucouleurs and induced Baudricourt to pledge neutrality. A few months later on October 12th, Orleans was placed under siege by an English army led by the Earl of Salisbury. The eyewitness accounts and other 15th century sources say that the situation for Charles was rather hopeless by that stage. His treasury at one point was down to less than "four ecus" and his armies were a motley collection of local contingents and foreign mercenaries and he himself, according to the surviving accounts, was torn with doubt over the validity of his cause - since his own mother, cooperating with the English, had allegedly declared him illegitimate in order to deny his claim to the throne. Orleans, the last major city defending the heart of his territory, was in the grip of an English army. Someone out of the ordinary was needed to reverse the fortunes and revive the failing cause of the last Valois and that someone was just setting out on a most improbable journey to take her place in history.

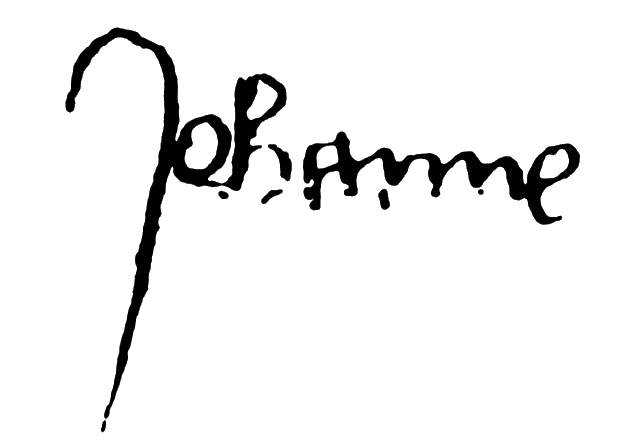

This situation facing the Armagnacs was indeed bleak and their embattled government was resident in the city of Chinon on the Vienne River when Joan, after her third attempt, was finally granted Baudricourt's permission to trsvel with an escort to travel to Chinon to speak with Charles. One account says that she convinced Baudricourt by accurately predicting an Armagnac defeat on 12 February 1429 near the village of Rouvray-Saint-Denis several miles north of Orleans. In this latest disaster, an army under the Count of Clermont took heavy losses while unsuccessfully attempting to stop an English supply convoy bringing food to their troops at the siege. When Baudricourt received confirmation of the predicted defeat he promptly arranged for an armed escort to bring Joan through enemy territory to Chinon. Adopting the standard procedure, her escorts dressed her in male clothing, partly as a disguise in case the group was captured (as a woman might be raped if her identity were discovered) and partly because such clothing had numerous cords with which the long boots and trousers could be tied to the tunic, which would offer an added measure of security. The eyewitnesses said she always kept this clothing on and securely tied together when encamped with soldiers, for safety and modesty's sake. She would call herself "La Pucelle" (the maiden or virgin), explaining that she had promised her saints to keep her virginity "for as long as it pleases God" and it is by this name that she is usually described in the 15th century documents. Chinon After eleven days on the road, Joan arrived at Chinon around March 4th, 1429 and was brought into Charles' presence, after a delay of two days, by Count Louis de Vendome. There are many eyewitness accounts of this event. Lord Raoul de Gaucourt, a Royal commander and bailiff of Orleans, recalled that "...she presented herself before his Royal majesty with great humility and simplicity, an impoverished little shepherd girl and ... said to the King: 'Most illustrious Lord Dauphin,  I have come and am sent in the name of God to bring aid to yourself and to the kingdom.'" The accounts indicate that she convinced Charles to take her seriously by telling him about a private prayer he had made the previous November 1st during which he had asked God to aid him in his cause if he was the rightful heir to the throne and to punish himself alone rather than his people if his sins were responsible for their suffering. She is said to have related the details of this prayer and assured him that he was the legitimate claimant to the throne. 'After hearing her', remembered one eyewitness, 'the King appeared radiant'. However, Charles first wanted her to be examined by a group of theologians in order to test her orthodoxy and for that purpose she was sent to the city of Poitiers about thirty miles to the south, where pro-Armagnac clergy from the University of Paris had fled after Paris and its university came under English control a decade earlier. They questioned her for three weeks before granting approval. A letter written by a Venetian named Pancrazio Giustiniani comments that her ability to hold her own against the learned theologians earned her a reputation as "another Saint Catherine come down to earth" and this reputation began to spread. While still at Poitiers Joan told a clergyman named Jean Erault to record an ultimatum to the English commanders at Orleans around March 22, the first of eleven surviving examples of the letters she dictated to scribes during the course of her military campaigns. This ultimatum begins with the "Jesus-Mary" slogan which would become her trademark, borrowed from the clergy known as "mendicants" - Dominicans, Franciscans, Carmelites and Augustinians - who made up a large portion of the priests in her army. She then goes on to inform the English that the "King of Heaven, Son of Saint Mary" supports Charles VII's claim to the throne and repeatedly advises the English to "go away to England" ("allez-vous-en en Angleterre") or she will "drive you out of France" ("bouter vous hors de France"). In lieu of a reply the English would detain the two messengers and Joan would find that more forceful methods would be needed to convince the English to pull their troops out of the Loire Valley. I have come and am sent in the name of God to bring aid to yourself and to the kingdom.'" The accounts indicate that she convinced Charles to take her seriously by telling him about a private prayer he had made the previous November 1st during which he had asked God to aid him in his cause if he was the rightful heir to the throne and to punish himself alone rather than his people if his sins were responsible for their suffering. She is said to have related the details of this prayer and assured him that he was the legitimate claimant to the throne. 'After hearing her', remembered one eyewitness, 'the King appeared radiant'. However, Charles first wanted her to be examined by a group of theologians in order to test her orthodoxy and for that purpose she was sent to the city of Poitiers about thirty miles to the south, where pro-Armagnac clergy from the University of Paris had fled after Paris and its university came under English control a decade earlier. They questioned her for three weeks before granting approval. A letter written by a Venetian named Pancrazio Giustiniani comments that her ability to hold her own against the learned theologians earned her a reputation as "another Saint Catherine come down to earth" and this reputation began to spread. While still at Poitiers Joan told a clergyman named Jean Erault to record an ultimatum to the English commanders at Orleans around March 22, the first of eleven surviving examples of the letters she dictated to scribes during the course of her military campaigns. This ultimatum begins with the "Jesus-Mary" slogan which would become her trademark, borrowed from the clergy known as "mendicants" - Dominicans, Franciscans, Carmelites and Augustinians - who made up a large portion of the priests in her army. She then goes on to inform the English that the "King of Heaven, Son of Saint Mary" supports Charles VII's claim to the throne and repeatedly advises the English to "go away to England" ("allez-vous-en en Angleterre") or she will "drive you out of France" ("bouter vous hors de France"). In lieu of a reply the English would detain the two messengers and Joan would find that more forceful methods would be needed to convince the English to pull their troops out of the Loire Valley.

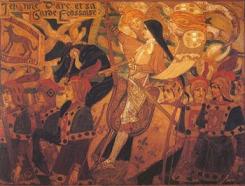

In 1429 Joan was provided with a suit of armour made, in the words of an eye witness, "exactly for her body". At this time Joan commissioned a Scottish painter Hauves Poulnoir, (Hamish Power), to design a large standard, Jhesus Maria, which was an image of "Our Savior" holding the world "with two angels at the sides" on a white background covered with gold fleurs-de-lis. He also designed a smaller pennant. Scotland's alliance with France at this time was particularly strong and there is even a claim that Joan might have trained in Scotland and Joan not only had In 1429 Joan was provided with a suit of armour made, in the words of an eye witness, "exactly for her body". At this time Joan commissioned a Scottish painter Hauves Poulnoir, (Hamish Power), to design a large standard, Jhesus Maria, which was an image of "Our Savior" holding the world "with two angels at the sides" on a white background covered with gold fleurs-de-lis. He also designed a smaller pennant. Scotland's alliance with France at this time was particularly strong and there is even a claim that Joan might have trained in Scotland and Joan not only had  Scot's in her army but also had a Scottish bodyguard. At this time, upon being brought to the army at Blois, a town about 35 miles southwest of Orleans, Joan had a third flag made with a scene of the crucifixion designed by Father Jean Pasquerel. It was here that she began to reform the troops and attempted to instil some discipline by expelling the prostitutes from the camp, sometimes at sword point according to several eyewitnesses. She also required the soldiers to go to church and confession, give up swearing and refrain from looting or harassing the civilian population. One astonished eyewitness reported that she succeeded in forcing a mercenary commander named Lord Etienne de Vignolles, known as "La Hire", meaning "anger" or "ire", to confess his sins to a priest. Her arrival had another valuable effect on the army. Word that a maid who was guided by Saints was now at the head of the army began to change minds and people for the first time believed victory could be won and men who would otherwise have refused to serve Charles' cause now began to volunteer. Their faith in Charles may have been equivocal, but they believed in La Pucelle, Joan. Scot's in her army but also had a Scottish bodyguard. At this time, upon being brought to the army at Blois, a town about 35 miles southwest of Orleans, Joan had a third flag made with a scene of the crucifixion designed by Father Jean Pasquerel. It was here that she began to reform the troops and attempted to instil some discipline by expelling the prostitutes from the camp, sometimes at sword point according to several eyewitnesses. She also required the soldiers to go to church and confession, give up swearing and refrain from looting or harassing the civilian population. One astonished eyewitness reported that she succeeded in forcing a mercenary commander named Lord Etienne de Vignolles, known as "La Hire", meaning "anger" or "ire", to confess his sins to a priest. Her arrival had another valuable effect on the army. Word that a maid who was guided by Saints was now at the head of the army began to change minds and people for the first time believed victory could be won and men who would otherwise have refused to serve Charles' cause now began to volunteer. Their faith in Charles may have been equivocal, but they believed in La Pucelle, Joan.

The army moved out from Blois around April 25th and arrived in stages at the besieged city between April 29th and May 4th. A small force had come out to meet them at Checy, five miles upriver from Orleans, but as there weren't enough barges to transport the entire body of troops across the river, Joan with a small group of soldiers were escorted into the city by Lord Jean d'Orleans (better known by his later title, Count of Dunois), the man in charge of the city's defense due to his status as the half-brother of the Duke of Orleans. The rest of the army would arrive later by a different route, its numbers greatly reduced by discouraged men who decided to leave without the Maiden there to encourage them.  On May 4th the rest of her troops made it into the city and a few hours later an assault was launched against an English-held fortified church called Saint Loup, about a mile east of Orleans. The surviving accounts say that the position was carried after Joan rode up with her banner, encouraging the troops up and over the ramparts. The English casualties totaled 114 dead and 40 captured. Sources from both factions quote her as saying that she preferred to carry her banner into battle, rather than a weapon, as is sometimes supposed, since, as she explained, she didn't want to harm anyone and there are many eyewitness accounts which repeatedly describe her encouraging the troops to greater efforts by placing herself in the same danger that they themselves faced. On May 4th the rest of her troops made it into the city and a few hours later an assault was launched against an English-held fortified church called Saint Loup, about a mile east of Orleans. The surviving accounts say that the position was carried after Joan rode up with her banner, encouraging the troops up and over the ramparts. The English casualties totaled 114 dead and 40 captured. Sources from both factions quote her as saying that she preferred to carry her banner into battle, rather than a weapon, as is sometimes supposed, since, as she explained, she didn't want to harm anyone and there are many eyewitness accounts which repeatedly describe her encouraging the troops to greater efforts by placing herself in the same danger that they themselves faced.

On the following day she sent her final ultimatum to the English commanders at Orléans, this time having an archer deliver the note with an arrow rather than risk losing another messenger. The remaining English positions fell swiftly. On May 6th an attack was made against a fortified monastery called the "Bastille des Augustins" which controlled the southern approach to a pair of towers called Les Tourelles, at the southern end of Orleans' bridge. Flanking these to the east was a fortified church called St-Jean-le-Blanc, near which the English had been bombarding the city with one of their largest cannons, called "le Passe-volant". The French troops were sent over a pontoon bridge around the hour of Tierce (9a.m.) and induced the English to abandon St-Jean-le-Blanc without a fight. The more substantial fortress of Les Augustins was then assaulted with Joan leading the initial charge alongside La Hire.  The fortress was then stormed and overrun with few losses. This placed Les Tourelles within striking range. During the course of the next morning's assault, Joan herself was wounded by an arrow while helping the soldiers set up a scaling ladder. It seems she stayed behind the area of fighting for most of the day but returned to the field near dusk in order to encourage the demoralized troops to one final effort which met with success and proved to be decisive. The English abandoned the siege the next day and moved to Meung-sur-Loire and other positions along the river. Orleans was the English high-water mark. Never again would they come so close to achieving a final victory against Charles, who would soon be anointed as King Charles VII. The fortress was then stormed and overrun with few losses. This placed Les Tourelles within striking range. During the course of the next morning's assault, Joan herself was wounded by an arrow while helping the soldiers set up a scaling ladder. It seems she stayed behind the area of fighting for most of the day but returned to the field near dusk in order to encourage the demoralized troops to one final effort which met with success and proved to be decisive. The English abandoned the siege the next day and moved to Meung-sur-Loire and other positions along the river. Orleans was the English high-water mark. Never again would they come so close to achieving a final victory against Charles, who would soon be anointed as King Charles VII.

The Loire Valley and Reims The unexpected lifting of the siege led to the support of a number of prominent figures. Duke Jean V of Brittany rejected his previous alliance with the English and promised to send troops to Charles' aid. The Archbishop of Embrun wrote a treatise [June 1429] declaring Joan to be divinely inspired and advised Charles to consult with her on matters concerning the war. The joy felt by Charles himself when he and Joan met again at Loches on the 11th was neatly summed up in an account by Eberhardt von Windecken: "... Then the young girl bowed her head before the King as much as she could and the King immediately had her raise it again and one would have thought that he would have kissed her from the joy that he experienced." On the other side, the English commander, the Duke of Bedford, reacted by calling up as many troops as possible from English occupied territory and the Duke of Burgundy made plans to take a more active role in helping his allies in the field, although as usual he demanded a modest sum (250,000 livres) to help offset his costs. After the Dauphin's joyful reunion with Joan she convinced him to take an army north to Reims to be crowned, as custom required. This was no simple task, since Reims at that time lay deep within enemy-held territory in order to open a way for a northward campaign, the Royal army first set about the job of clearing out the remaining English positions in the Loire Valley, with the Duke of Alencon being given command of the venture. The army's first target was Jargeau, ten miles to the southeast of Orleans. At least 3,600 armored troops, plus an unknown number of lightly-armed 'commons', were present for duty. The town was reached on June 11th. The main assault came the next day after an artillery bombardment in which Jargeau's largest tower was felled by a large cannon from Orleans nicknamed "La Bergere" ("the Shepherdess"), presumably named after Joan herself.  The latter's role was also crucial: carrying her banner up front with the troops, she was hit in the helmet with a stone but immediately got back on her feet and encouraged the soldiers to storm the ramparts by shouting: "Friends, friends, up! Up! Our Lord has condemned the English". [In the archaic French of the 15th century: "Amys, amys, sus! Sus! Nostre Sire a condempne les Angloys"] The fortifications were taken and the English were driven back across Jargeau's bridge. The survivors surrendered.

The latter's role was also crucial: carrying her banner up front with the troops, she was hit in the helmet with a stone but immediately got back on her feet and encouraged the soldiers to storm the ramparts by shouting: "Friends, friends, up! Up! Our Lord has condemned the English". [In the archaic French of the 15th century: "Amys, amys, sus! Sus! Nostre Sire a condempne les Angloys"] The fortifications were taken and the English were driven back across Jargeau's bridge. The survivors surrendered.

Beaugency was taken on the 17th after the English garrison negotiated an agreement allowing them to withdraw. That evening the English troops at Meung, reinforced by an army under Sir John Fastolf, offered battle to the French but subsequently decided to fall back the next day, riding northward in an effort to make it back to more secure territory. The French pursued (goaded on by Joan saying that they should use their "good spurs" to chase the enemy). The two armies clashed south of Patay, where a rapid cavalry charge led by La Hire and other nobles of the vanguard overran a unit of 500 English archers who had been set up to delay the French as long as they could. Confusion among the main contingents of the English army completed the rout and the French cavalry swept their opponents from the field. The English heralds announced their losses at 2,200 men, compared to only three casualties for the French - the reverse of so many other battles during that war. The March to Reims When Charles met his commanders after this victory, the decision was made to press on northward to Reims.  Gathering the army together at Gien on the Loire, both Charles and Joan began sending out letters requesting various cities and dignitaries to send representatives to the coronation. The Royal army finally moved out from Gien on the 29th, after a delay which caused Joan much distress. The Burgundian-held city of Auxerre was reached the next day and an agreement with the city leaders was worked out after three days of negotiations: the army was allowed to buy food and Auxerre agreed to pay the same obedience to Charles as Troyes, Chalons and Reims chose to do. The next stop was Troyes, garrisoned by 500-600 Burgundian troops. Gathering the army together at Gien on the Loire, both Charles and Joan began sending out letters requesting various cities and dignitaries to send representatives to the coronation. The Royal army finally moved out from Gien on the 29th, after a delay which caused Joan much distress. The Burgundian-held city of Auxerre was reached the next day and an agreement with the city leaders was worked out after three days of negotiations: the army was allowed to buy food and Auxerre agreed to pay the same obedience to Charles as Troyes, Chalons and Reims chose to do. The next stop was Troyes, garrisoned by 500-600 Burgundian troops.

On July 4th, at St. Phal near Troyes, she sent a letter to the citizens of Troyes asking them to declare themselves for Charles, adding that "with the help of King Jesus", Charles will enter all of the towns within his inheritance regardless of their wishes. Troyes initially ignored the summons. While Charles' commanders debated their next course of action, Joan told them to promptly besiege the town, predicting they would gain it in three days "either by love or by force". Lord Dunois remembered that she then began ordering the placement of the troops and did it so well that "two or three of the most famous and experienced soldiers" could not have done it better. Troyes surrendered the next day without a fight. The Royal army entered on the 10th. By the 14th it had reached Chalons-sur-Marne to the north which opened its gates with greater promptitude than Troyes. Reims followed suit after Joan counseled Charles to "advance boldly" and now the Dauphin was poised to receive the crown which had been denied him years earlier.  During the ceremony Joan stood near Charles, holding her banner. The memorable words of one 15th century source describes the scene after Charles was crowned, Joan "wept many tears and said, 'Noble king, now is accomplished the pleasure of God, who wished me to lift the siege of Orleans and to bring you to this city of Reims to receive your holy anointing, to show that you are the true king and the one to whom the kingdom of France should belong.'" It adds: "All those who saw her were moved to great compassion." During the ceremony Joan stood near Charles, holding her banner. The memorable words of one 15th century source describes the scene after Charles was crowned, Joan "wept many tears and said, 'Noble king, now is accomplished the pleasure of God, who wished me to lift the siege of Orleans and to bring you to this city of Reims to receive your holy anointing, to show that you are the true king and the one to whom the kingdom of France should belong.'" It adds: "All those who saw her were moved to great compassion."

The Siege of Paris On July 17th, the day of the coronation, Joan sent a letter to the Duke of Burgundy asking why he did not attend the coronation and proposing that he and Charles should "make a good firm lasting peace. Pardon each other completely and willingly as loyal Christians should do and if it should please you to make war, go against the Saracens." (The Islamic Saracens, frequently at war with Christendom, were one of her preferred targets for legitimate military action). Although the Duke himself stayed away, his emissaries had arrived in Reims on the day of the coronation and began negotiations which resulted in a 15-day truce being declared - not exactly the "good, firm, lasting peace" that Joan wanted and in fact such a short truce immediately following in the wake of Charles' triumph could serve only to give the English and Burgundians time to regroup. Charles followed up this treaty by taking his army on a city-by-city tour of the Ile-de-France, accepting the loyalty of each in turn. Near Crepy-en-Valois, Joan was quoted as saying that she now hoped that God would permit her to return to her family's home. The army of the Duke of Bedford was nearby, however - Bedford had recently sent off a challenge to Charles VII asking him to meet the English at "some place in the fields, convenient and reasonable" for a showdown. The place turned out to be the village of Montpilloy just southwest of Crepy, where the two armies clashed on August 14th and 15th, with Joan herself going so far as to lead a charge against the English fortified positions to try to draw them out but only a prolonged series of skirmishes took place and both armies withdrew on the night of the 15th.  The French went back to Crepy and then proceeded on to Compiegne to the northwest. At the same time negotiations with the Burgundians were getting underway, with the positions of the two parties oddly reversed: while French armies were rapidly advancing, the French delegation was offering sweeping concessions, bargaining as if they were on the losing side. On the 21st a treaty was signed providing for a four-month truce designed to prevent the Royal army from continuing its offensive, coupled with the added provision that several towns should be handed over to the Duke of Burgundy. A peace conference was promised for the spring, although the documents show that the English were preparing to launch an offensive around the same time. Meanwhile, King Charles remained at Compiegne. On the 23rd Joan and the Duke of Alencon left on their own initiative with a body of troops and made their way to the region around Paris, arriving at St-Denis on the 25th and sending out skirmishers "up to the gates of Paris" over the next several days. A brief siege began on September 8th, but Joan was hit in the thigh that day by a crossbow dart while trying to find a place for her troops to cross the city's inner moat. She was carried back against her will, all the while urging on another assault. No further attack would be forthcoming. On the 9th the army was ordered back to St-Denis where the King was located by that point when he learned that the commanders were thinking of crossing back to Paris by a bridge constructed on the orders of the Duke of Alencon, Charles ordered the bridge destroyed. On the 13th the troops began the discouraging march back to the Loire. On September 21st the army, by then back at Gien, was disbanded. The Duke of Alencon's squire and chronicler, Perceval de Cagny, summed up this event with the terse and bitter statement: "And thus was broken the will of the Maiden and the King's army." Like many of those who had served in that army, Cagny tended to feel that the disastrous policies promoted by the Royal counselors - most blamed Georges de la Tremoille in particular - had fatally undermined Joan 's successes. The commanders were dispersed to their own estates or former areas of operations. When the Duke of Alencon, preparing a campaign into Normandy, asked that Joan of Arc be allowed to join him, the Royal court refused. The French went back to Crepy and then proceeded on to Compiegne to the northwest. At the same time negotiations with the Burgundians were getting underway, with the positions of the two parties oddly reversed: while French armies were rapidly advancing, the French delegation was offering sweeping concessions, bargaining as if they were on the losing side. On the 21st a treaty was signed providing for a four-month truce designed to prevent the Royal army from continuing its offensive, coupled with the added provision that several towns should be handed over to the Duke of Burgundy. A peace conference was promised for the spring, although the documents show that the English were preparing to launch an offensive around the same time. Meanwhile, King Charles remained at Compiegne. On the 23rd Joan and the Duke of Alencon left on their own initiative with a body of troops and made their way to the region around Paris, arriving at St-Denis on the 25th and sending out skirmishers "up to the gates of Paris" over the next several days. A brief siege began on September 8th, but Joan was hit in the thigh that day by a crossbow dart while trying to find a place for her troops to cross the city's inner moat. She was carried back against her will, all the while urging on another assault. No further attack would be forthcoming. On the 9th the army was ordered back to St-Denis where the King was located by that point when he learned that the commanders were thinking of crossing back to Paris by a bridge constructed on the orders of the Duke of Alencon, Charles ordered the bridge destroyed. On the 13th the troops began the discouraging march back to the Loire. On September 21st the army, by then back at Gien, was disbanded. The Duke of Alencon's squire and chronicler, Perceval de Cagny, summed up this event with the terse and bitter statement: "And thus was broken the will of the Maiden and the King's army." Like many of those who had served in that army, Cagny tended to feel that the disastrous policies promoted by the Royal counselors - most blamed Georges de la Tremoille in particular - had fatally undermined Joan 's successes. The commanders were dispersed to their own estates or former areas of operations. When the Duke of Alencon, preparing a campaign into Normandy, asked that Joan of Arc be allowed to join him, the Royal court refused.

Winter During this period of inactivity, Joan was moved around to various residences of the Royal court, such as at Bourges and Sully-sur-Loire. The next military venture, albeit a fairly small one, was the attack against Saint-Pierre-le-Moutier, which was captured on November 4. Jean d'Aulon, Joan 's squire and bodyguard, remembered that the initial assault was a failure and the soldiers in full retreat, except for Joan herself and a handful of men clustered around her.  He rode up to her and told her to fall back with the rest of the army, but she refused, declaring that she had "fifty-thousand" troops with her. Shouting for the army to bring up bundles for filling in the town's moat, she initiated a new assault which took

the objective "without much resistance", according to the astonished d'Aulon. He rode up to her and told her to fall back with the rest of the army, but she refused, declaring that she had "fifty-thousand" troops with her. Shouting for the army to bring up bundles for filling in the town's moat, she initiated a new assault which took

the objective "without much resistance", according to the astonished d'Aulon.

The next target was the town of La-Charite-sur-Loire. Since the army was undersupported by the Royal court, she sent letters off to nearby cities asking them to donate supplies. Clermont-Ferrand responded by sending two hundredweight of saltpeter, an equal amount of sulfur and two bundles of arrows. The siege of La Charite was a dismal failure. The weather was cold and the army had "few men" and the Royal court did little to provide support for the troops ("the King", according to Cagny, "made no diligence to send her food supplies nor money to maintain her army"). The army withdrew after a month, abandoning their artillery. Joan spent the rest of the winter at various Royal estates while the English and Burgundians regrouped for a new campaign. The month of March 1430 saw a flurry of letters being sent out by Joan, all of them dictated in the town of Sully-sur-Loire. Two of these, on the 16th and 28th, went to the citizens of Reims, assuring them that she would aid them in the event of a siege. On March 23rd she sent an ultimatum to the Hussites, addressed as "the heretics of Bohemia", warning that she would lead a crusading army against them unless they "return to the Catholic faith and the original Light". However, it is likely that this letter was not written by Joan but by Pasquerel and sent with her acquiescence. In late March or early April Joan of Arc finally took the field again with her small group (her brother Pierre, her confessor Friar Jean Pasquerel, her bodyguard Jean d'Aulon and a few others), escorted by a mercenary unit of about 200 troops led by Bartolomew Baretta of Italy. They headed for Lagny-sur-Marne, where French forces were putting up a fight against the English. Around Easter (April 22nd) she was at Melun where, as she would later say, her saints had revealed to her that she would be captured "before Saint John's Day" (June 24). She had said at many points that capture and betrayal were her greatest fears. Meanwhile, the Burgundian army was on the move despite all the promises of peace and on May 6th Charles VII and his counselors finally admitted that the Royal Court had been manipulated by the Duke, "...who has diverted and deceived us by truces and otherwise", as Charles wrote in a letter on that date. He would now order a damaging series of assaults on Burgundian territory to the east, but in the northeast the Armagnacs were in trouble. The Duke of Burgundy was now there in force. His strategy, based on an elaborate document outlining his plans, called for the bridge at Choisy-au-Bac to be taken, followed by the monastery at Verberie and then a methodical series of assaults to block all the supply routes into Compiegne, which had refused to submit to him under the terms of the agreement signed the previous year. Choisy-au-Bac was taken on May 16th on the 22nd and the Duke laid siege to Compiègne. Joan was unwilling to let this city, which had showed such courage in its defiance, fall unaided. Reinforced with 300 - 400 additional troops picked up at Crepy-en-Valois, on the morning of the 23rd at sunrise she and her tiny army slipped into Compiegne.  She apparently knew what was coming according to the later statements of two men who had, as young boys, been among a group of curious children watching Joan pray in one of Compiegne's churches that morning. She was much troubled in spirit and told the children to "pray for me for I have been betrayed". Later that day she was among those leading a sortie against the enemy camp at Margny when her troops were ambushed by Burgundian forces concealed behind a hill called the Mont-de-Clairoix. Having decided to stay with the rearguard during the retreat, she and her soldiers were trapped outside the city and pinned up against the river when the drawbridge was prematurely raised behind them. Burgundian troops swarmed around her, each asking her to surrender. She refused and was finally pulled off her horse by an enemy archer. A nobleman named Lionel of Wandomme, in the service of John of Luxembourg, made her his captive. A Burgundian chronicler who was present, Enguerrand de Monstrelet, wrote that the Armagnacs were devastated by Joan 's capture, while the English and Burgundians were "overjoyed, more so than if they had taken 500 combatants, for they had never feared or dreaded any other commander... as much as they had always feared this maiden up until that day." The garrison commander at Compiegne, Guillaume de Flavy, came under immediate suspicion as a traitor, although his guilt was never proved. Since the Royal Court at that time was divided into factions, each of which routinely tried to eliminate any prominent leader who was supported by their rivals, it would be likely that a small group within the Court may have betrayed her. The evidence indicates that Charles VII probably was not among the guilty, however, nor did he abandon her, as is so often claimed. According to the archives of the Morosini, who were in contact with the Royal Court, Charles VII tried to force the Burgundians to return Joan in exchange for the usual ransom and threatened to treat Burgundian prisoners according to whatever standard was adopted in Joan 's case. The pro-Anglo-Burgundian University of Paris, which later helped arrange her conviction, sent an alarmed letter to John of Luxembourg reporting that the Armagnacs were "doing everything in their power" to try to get her back. Dunois and La Hire would lead four campaigns during that winter and the following spring which seem to have been designed to rescue her by military means.

These attempts failed and the Burgundians refused to ransom her.

She apparently knew what was coming according to the later statements of two men who had, as young boys, been among a group of curious children watching Joan pray in one of Compiegne's churches that morning. She was much troubled in spirit and told the children to "pray for me for I have been betrayed". Later that day she was among those leading a sortie against the enemy camp at Margny when her troops were ambushed by Burgundian forces concealed behind a hill called the Mont-de-Clairoix. Having decided to stay with the rearguard during the retreat, she and her soldiers were trapped outside the city and pinned up against the river when the drawbridge was prematurely raised behind them. Burgundian troops swarmed around her, each asking her to surrender. She refused and was finally pulled off her horse by an enemy archer. A nobleman named Lionel of Wandomme, in the service of John of Luxembourg, made her his captive. A Burgundian chronicler who was present, Enguerrand de Monstrelet, wrote that the Armagnacs were devastated by Joan 's capture, while the English and Burgundians were "overjoyed, more so than if they had taken 500 combatants, for they had never feared or dreaded any other commander... as much as they had always feared this maiden up until that day." The garrison commander at Compiegne, Guillaume de Flavy, came under immediate suspicion as a traitor, although his guilt was never proved. Since the Royal Court at that time was divided into factions, each of which routinely tried to eliminate any prominent leader who was supported by their rivals, it would be likely that a small group within the Court may have betrayed her. The evidence indicates that Charles VII probably was not among the guilty, however, nor did he abandon her, as is so often claimed. According to the archives of the Morosini, who were in contact with the Royal Court, Charles VII tried to force the Burgundians to return Joan in exchange for the usual ransom and threatened to treat Burgundian prisoners according to whatever standard was adopted in Joan 's case. The pro-Anglo-Burgundian University of Paris, which later helped arrange her conviction, sent an alarmed letter to John of Luxembourg reporting that the Armagnacs were "doing everything in their power" to try to get her back. Dunois and La Hire would lead four campaigns during that winter and the following spring which seem to have been designed to rescue her by military means.

These attempts failed and the Burgundians refused to ransom her.

The Trial After four months spent as a prisoner in the chateau of Beaurevoir, Joan was transferred to the English in exchange for 10,000 livres, an arrangement similar to the standard practice in other cases of prisoner transfers between members of the same side, such as when Henry V had paid his nobles for transferring their prisoners to him after the battle of Agincourt. Pierre Cauchon, a longtime supporter of the Anglo-Burgundian faction, was given the job of procuring her and setting up a trial. He had been given many such tasks in the past. A letter from Duke John-the-Fearless of Burgundy, dated 26th July 1415, authorized Cauchon to bribe Church officials at the Council of Constance in order to influence the Council's ruling concerning a murder which the Duke had ordered. They now needed someone who was willing to engineer a murder under the guise of an Inquisitorial trial and Cauchon again got the job.  English government documents record in great detail the payments made to cover the costs of obtaining Joan and rewarding the various judges and assessors who took part in her trial and we know that the clergy who served at the trial were drawn from their supporters. Some of these men later admitted that the English conducted the proceedings for the purposes of revenge rather than out of any genuine belief that she was a heretic. Joan was held at the fortress of Crotoy before being brought to Rouen, the seat of the English occupation government. Although Inquisitorial procedure required suspects to be held in a Church-run prison and female prisoners to be guarded by nuns rather than male guards (for obvious reasons), Joan was held in a secular military prison with English soldiers as guards. According to several eyewitness accounts it was for this reason that she clung to her soldiers' outfit and kept the pants and tunic "firmly laced and tied together" as a defense against rape: the trial transcript says that she wore two layers of such pants, both attached to the tunic with a total of over two dozen cords and many eyewitnesses said that this was now her only means of defending herself against rape since a dress didn't offer any such protection. The tribunal eventually decided to use this against her by charging that it violated the prohibition against cross-dressing, a charge which intentionally ignored the exemption allowed in such cases of necessity by medieval doctrinal sources such as the "Summa Theologica" and "Scivias". English government documents record in great detail the payments made to cover the costs of obtaining Joan and rewarding the various judges and assessors who took part in her trial and we know that the clergy who served at the trial were drawn from their supporters. Some of these men later admitted that the English conducted the proceedings for the purposes of revenge rather than out of any genuine belief that she was a heretic. Joan was held at the fortress of Crotoy before being brought to Rouen, the seat of the English occupation government. Although Inquisitorial procedure required suspects to be held in a Church-run prison and female prisoners to be guarded by nuns rather than male guards (for obvious reasons), Joan was held in a secular military prison with English soldiers as guards. According to several eyewitness accounts it was for this reason that she clung to her soldiers' outfit and kept the pants and tunic "firmly laced and tied together" as a defense against rape: the trial transcript says that she wore two layers of such pants, both attached to the tunic with a total of over two dozen cords and many eyewitnesses said that this was now her only means of defending herself against rape since a dress didn't offer any such protection. The tribunal eventually decided to use this against her by charging that it violated the prohibition against cross-dressing, a charge which intentionally ignored the exemption allowed in such cases of necessity by medieval doctrinal sources such as the "Summa Theologica" and "Scivias".  The eyewitnesses said that Joan pleaded with Cauchon to transfer her to a Church prison with women to guard her, in which case she could safely wear a dress but this was never allowed. The trial included a series of hearings from February 21st through the end of March 1431. Normally, Inquisitorial tribunals were supposed to hear witness testimony against the accused and base any verdict upon such testimony, but in this case the only witness called was the accused herself. The trial assessors, as a number of them later admitted, therefore resorted to trying to manipulate her into saying something that might be used against her. There were other profound deviations from lawful procedure. As many historians have pointed out, the theological arguments put forward by Cauchon and his associates are mostly a set of subtle half-truths, not only on the "cross-dressing" charge but also concerning issues such as the authority of the tribunal: standard Inquisitorial procedure required such tribunals to be overseen by non-partisan judges, otherwise the trial could be automatically rendered null and void. Similarly, the accused was allowed to appeal to the Pope. The eyewitnesses said Joan repeatedly asked for both of these rules to be honored, but this was never granted. They stated that she had submitted to the authority of both the Papacy and the Council of Basel, but the latter was left out of the transcript on Cauchon's orders and the former was entered in a form which distorted her statements on the matter. The dispute between Joan and her judges therefore largely revolved around the legitimacy of the tribunal as an impartial jury of the Church Universal and medieval ecclesiastic law is on her side. The eyewitnesses said that Joan pleaded with Cauchon to transfer her to a Church prison with women to guard her, in which case she could safely wear a dress but this was never allowed. The trial included a series of hearings from February 21st through the end of March 1431. Normally, Inquisitorial tribunals were supposed to hear witness testimony against the accused and base any verdict upon such testimony, but in this case the only witness called was the accused herself. The trial assessors, as a number of them later admitted, therefore resorted to trying to manipulate her into saying something that might be used against her. There were other profound deviations from lawful procedure. As many historians have pointed out, the theological arguments put forward by Cauchon and his associates are mostly a set of subtle half-truths, not only on the "cross-dressing" charge but also concerning issues such as the authority of the tribunal: standard Inquisitorial procedure required such tribunals to be overseen by non-partisan judges, otherwise the trial could be automatically rendered null and void. Similarly, the accused was allowed to appeal to the Pope. The eyewitnesses said Joan repeatedly asked for both of these rules to be honored, but this was never granted. They stated that she had submitted to the authority of both the Papacy and the Council of Basel, but the latter was left out of the transcript on Cauchon's orders and the former was entered in a form which distorted her statements on the matter. The dispute between Joan and her judges therefore largely revolved around the legitimacy of the tribunal as an impartial jury of the Church Universal and medieval ecclesiastic law is on her side.

Early in the trial an attempt was made to link her to witchcraft by claiming her banner had been endowed with "magical" powers, that she allegedly poured wax on the heads of small children and other accusations of this sort, but these charges were dropped before the final articles of accusation were drawn up on April 5th. In one of the more curious bids to discredit her, Cauchon objected to her use of the "Jesus-Mary" slogan which, somewhat paradoxically, was used by the Dominicans who largely ran the Inquisitorial courts. Her saints were dismissed as "demons", despite the transcript's own description that they had counseled her to "go regularly to Church" and maintain her virginity. In the end, Cauchon would convict her on the cross-dressing charge, which he utilized in a manner which gives an indication of his character. According to several eyewitnesses - the trial bailiff Jean Massieu, the chief notary Guillaume Manchon, the assessors Friar Martin Ladvenu and Friar Isambart de la Pierre and the Rouen citizen Pierre Cusquel - after Joan had finally consented to wear a dress, her guards immediately increased their attempts to rape her, joined by "a great English lord" who tried to do the same. Her guards finally took away her dress entirely and threw her the old male clothing which she was forbidden to wear, sparking a bitter argument between Joan and the guards that "went on until noon", according to the bailiff. She had no choice but to put on the clothing left to her, after which Cauchon promptly pronounced her a "relapsed heretic" and condemned her to death. Several eyewitnesses remembered that Cauchon came out of the prison and exclaimed to the Earl of Warwick and other English commanders waiting outside, "Farewell, be of good cheer, it is done!", implying that he had orchestrated the trap that the guards had set for her. The scene of her execution is vividly described by a number of those who were present that day. She listened calmly to the sermon read to her, but then broke down weeping during her own address in which she forgave her accusers for what they were doing and asked them to pray for her. The accounts say that most of the judges and assessors themselves and a few of the English soldiers and officials were openly sobbing by the end of it.  But a few of the English soldiers were becoming impatient and one sarcastically shouted to the bailiff Jean Massieu, "What, priest, are you

going to make us wait here until dinner?" The executioner was ordered to "do your duty". They tied her to a tall pillar well above the crowd. She

asked for a cross, which one sympathetic English soldier tried to provide by making a small one out of wood. A crucifix was brought from the nearby church and Friar Martin Ladvenu held it up in front of her until the flames rose. Several eyewitnesses recalled that she repeatedly screamed "...in a loud voice the holy name of Jesus and implored and invoked without ceasing the aid of the saints of Paradise". Then her head drooped and it was over. Jean Tressard, Secretary to the King of England, was seen returning from the execution exclaiming in great agitation, "We are all ruined,

for a good and holy person was burned." The Cardinal of England himself and the Bishop of Therouanne, brother of the same John of Luxembourg whose troops had captured Joan, were said to have wept bitterly. The executioner, Geoffroy Therage, confessed to Martin Ladvenu and Isambart de la Pierre afterwards, saying that "...he had a great fear of being damned [as] he had burned a saint." The worried English authorities tried to put a stop to any further talk of this sort by punishing those few who were willing to publicly speak out in her favor and the records show a number of prosecutions during the following days. But a few of the English soldiers were becoming impatient and one sarcastically shouted to the bailiff Jean Massieu, "What, priest, are you

going to make us wait here until dinner?" The executioner was ordered to "do your duty". They tied her to a tall pillar well above the crowd. She

asked for a cross, which one sympathetic English soldier tried to provide by making a small one out of wood. A crucifix was brought from the nearby church and Friar Martin Ladvenu held it up in front of her until the flames rose. Several eyewitnesses recalled that she repeatedly screamed "...in a loud voice the holy name of Jesus and implored and invoked without ceasing the aid of the saints of Paradise". Then her head drooped and it was over. Jean Tressard, Secretary to the King of England, was seen returning from the execution exclaiming in great agitation, "We are all ruined,

for a good and holy person was burned." The Cardinal of England himself and the Bishop of Therouanne, brother of the same John of Luxembourg whose troops had captured Joan, were said to have wept bitterly. The executioner, Geoffroy Therage, confessed to Martin Ladvenu and Isambart de la Pierre afterwards, saying that "...he had a great fear of being damned [as] he had burned a saint." The worried English authorities tried to put a stop to any further talk of this sort by punishing those few who were willing to publicly speak out in her favor and the records show a number of prosecutions during the following days.

It would not be until the English were finally driven from Rouen in November of 1449, near the end of the war, that the slow process of appealing the case would be initiated.  This process resulted in a posthumous acquittal by an Inquisitor named Jean Bréhal, who paradoxically had been a member of an English-run institution during the war. Bréhal nevertheless ruled that she had been convicted illegally and without basis by a corrupt court operating in a spirit of "...manifest malice against the Roman Catholic Church and indeed heresy". The Inquisitor and other theologians consulted for the appeal therefore denounced Cauchon and the other judges and described Joan as a martyr, thereby paving the way for her eventual beatification in 1909 and canonization as a saint in 1920, by which time even English writers and clergy no longer showed the opposition that their predecessors had. During the Great War 1914-18, in the midst of the canonization process and a period of French-English detente, Allied soldiers would pay tribute to the heroine by invoking her name on battlefields not far from the battle grounds that Joan herself fought on. This process resulted in a posthumous acquittal by an Inquisitor named Jean Bréhal, who paradoxically had been a member of an English-run institution during the war. Bréhal nevertheless ruled that she had been convicted illegally and without basis by a corrupt court operating in a spirit of "...manifest malice against the Roman Catholic Church and indeed heresy". The Inquisitor and other theologians consulted for the appeal therefore denounced Cauchon and the other judges and described Joan as a martyr, thereby paving the way for her eventual beatification in 1909 and canonization as a saint in 1920, by which time even English writers and clergy no longer showed the opposition that their predecessors had. During the Great War 1914-18, in the midst of the canonization process and a period of French-English detente, Allied soldiers would pay tribute to the heroine by invoking her name on battlefields not far from the battle grounds that Joan herself fought on.

Joan's story may be brief but is nonetheless an historic journey. Setting out on a cold February day in 1429, travelling through territory held by the enemies of the Dauphin Charles, to tell him that God, through the Saints, had instructed her to seek the 'Rightful heir' to the French throne and that she, a seventeen year old maiden, would raise the siege at Orleans, lead him to be crowned at Reims as tradition demanded if he were to be considered the lawful King of France and finally that she would drive the English from all the lands of France. A story as improbable as it is inspiring. Successive centuries have only served to increase the legend and Joan has provided inspiration through her glory, given hope through her faith and by her courage bestowed pride upon her country. Her story is also rare in that records by both sides in the conflict are available and are in general agreement, attesting to the consistency of her beliefs, the intelligence of her words and the courage that she displayed right to her heroic end. Her statues are regularly adorned with flowers and wreaths, writers and film makers are still drawn to her story. Her faith and courage reach far beyond it's 15th century regional setting. France, if ever in want of courage need only look to the greatest of heroines, Joan of Arc, maiden, patriot, soldier and Saint. |

|

|

Above is a photo taken in 2012, the six hundredth anniversary of Joan of Arc's birthday, of her statue at the Place des Pyramides in Paris. The statue was dedicated in 1872 and erected in 1874 mainly to bolster France's confidence after her defeat in the 1870 war with Prussia. However, this is not the original horse as the sculptor Emmanuel Fremiet was not happy with the scale of horse to rider and took the unusual course of altering a work of art after it had been displayed publicly, replacing it with a copy of the horse he had designed for Joan of Arc's statue in Nancy.

|

Track 1, a Gregorian Chant version of O.M.D.'s Joan of Arc (Maid of Orleans) would befit any memorial service for Joan.

Track 2 is the theme music from The Messenger - The Story of Joan Of Arc.

Track 3, La marche des soldats de Robert Bruce was played at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 when Scotland's army routed a much larger English force and also for Joan of Arc's triumphant entry into the city of Orleans on April 29th, 1429.

Track 4 is an extended version of O.M.D.'s inspired single from their Architecture and Morality album, Joan of Arc (Maid of Orleans). This may seem an unlikely candidate as an 'anthem' for Joan of Arc but it's stirring bagpipe effect and martial drum beat invoke the spirit of Joan's life and the Hundred Years War in general and shows how she still reaches and inspires far beyond France's borders.

Update Required

To play the media you will need to either update your browser to a recent version or update your Flash plugin.